How to lengthen the IT Band?

Start by loosening and lengthening the pelvic muscles and hamstrings and calves, also the adductors, and those leg releases will help the pelvic muscles to loosen all around. Do twist stretching of thighs and pelvis. Then you can do a pull from over your head pulling one arm with another and bending in a bow, pushing out first the shoulder, then rest, then push out the ribs, then rest, then push out the waist and pelvis, then do the outer thigh. But you have to loosen around the pelvic muscles because they control that tendon.

I do the IT band lengthening regularly for clients by lengthening the fascia with hands on and we can often do it with a stretching relengthening of the fascial element of the muscles that govern the movement of this long tendon, and with the fascia that covers that tendon, and into the muscles interconnecting it with the rest of the leg in the whole bodysuit of the fascia. You CAN spread the fascial element covering the tendon if you also spread the fascia of the pelvic muscles involved and also lengthen the fascia of the hamstrings and adductors, and some of the lower leg muscle fascia, too.

How to massage it? You can massage, then stretch, or try the connective tissue manipulation spreading techbnique.

Have the person, or you, yourself, push deep into the muscles in the buttocks and front groin of the pelvis on top of the quads on the front of the thigh. Dig into the muscles so you can push your fingers thru the tissue instead of sliding over it. Get the muscle putty, which is the fascia interspersed on a microscopic level with the muscle fibers. The whole thing can widen, soften and lengthen. Then do the smooshing down the outside of the the thigh and under the legs in the hamstrings. That part, the hamstrings is often more difficult to achieve. Have a hot bath or hot shower on it, or a hot pack to soften up the muscle-nerve-blood tightness so you can just work on the putty spreading lement. You may also do massaging on the areas first and then try the spreading motion. Below, I give more principles and some more muscles to work.

It can lengthen, and people feel taller on the one side of the body that is done first.

Further if you lengthen the outer lower leg, including the peroneals, you’ll get better results in the thigh and pelvis. It’s a long interconnected fascial network of one big piece. You want it ALL to give way in a spreading way when you pull area by area with stretching and then smoosh it with your fingers or knuckles or get someone else’s arm and hands to do it. Be careful on the IT band itself though - do NOT push harshly into it, just spread small layer at a time lengthwise down the tendon or across it. We aren’t trying to force anything to “let go.” Instread, we are simply trying to spread shortened putty back longer agin. The skills involved are to be able to do the special kind of manipulation and to know where to work and in what order.

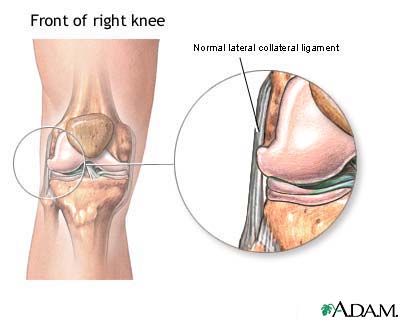

Here we have a two-joint muscle tendon mechanism. The gluteals and tensor muscles tighten and pull the tendon across the hip and knee joints to stabilize the leg, whenever we stand on one leg, including when we are walking and running.

Please see my long explanation just above in another forum entry As I said, we thus have to lengthen the gluteals, including the medius and minimus on the outside of the pelvis from the greater trochanter to the illiac bone crest. They, and the two other muscles are on the top end of the trochanter and this tendon you want to loosen is on the bottom end.

You’ll also get better results if you also lengthen the abdominals, the long muscles of the back, and the psoas and adductors. If you find someone who can spread the fascia of the illiacus inside your pelvic illium bone crests, that’ll help the IT band and all the leg muscles even more. See entry above for more info.

Consult an anatomy book so you can see what is connected to what, and simply relengthen or get massaged out, what you have bunched up with your running or weight workouts. Just spread in the opposite direction. Ida P. Rolf’s big “Rolfing” book has a good sketch, and it explains about fascia. So do the articles on my website http://www.backfixbodywork.com . See Fixing Accumulated Shortness article sections 2 and 3 to have a detailed explanation of fascia-muscle anatomy. The above entry also indicates other helpful, informative articles to read. Rolf was a PhD physiologist-biochemist and a pioneer who took the fascial release method and extended it into a structural architectural bigger understanding. There is a good book by a couple of senior level Rolfers, called The Endless Web, describing the body’'s fascial network, with a lot of good illustrations of muscle bone networks as well.

You can look up the Rolf Institute on the web and get the books from their bookstore, and also maybe Amazon.

If your massage therapist likes to help by doing PNF stretching, which has the nerve signals turn off and the muscle fiber reflexes release, to get a onger stretch. Then relengthening the fascial envelopes will make the PNF stretch help the nerve-muscle release to give you a better stretch that way, too. I’ve even experienced foot reflexology to cause a big release of the whole body tightness when the fascia of the whole body had already been lengthening and some activity, reflexes or digestive imbalances had been holding the muscle fiber elements short.